|

"SuperCroc" Fossil Found in Sahara

D.L. Parsell

National Geographic News

September 05, 2003

Hey, Crocodile Dundee, try this on for size.

Scientists have unearthed the remains of an ancient crocodile that was as long as a city bus and as heavy as a small whale.

The giant creature, which lived 110 million years ago, during the Middle Cretaceous, grew as long as 40 feet (12 meters) and weighed as much as eight metric tons (17,500 pounds).

Its jaws alone were nearly six feet (1.8 meters) long and its more than 100 teeth so powerful that the colossal creature probably consumed small dinosaurs as well as fish, the researchers say.

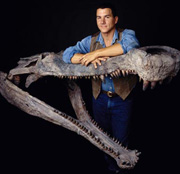

Paleontologist Paul Sereno and his colleagues pieced together a portrait of the monsterwhich they've dubbed SuperCrocbased on fossils they've collected at Gadoufaoua in Niger, a remote site in the Sahara Desert where Tuareg nomads roam.

The fossils are from an extinct species that first came to light more than 30 years ago. French paleontologists reported several skulls and other parts of the creature and named it Sarcosuchus imperator, meaning "flesh crocodile emperor."

Much about the giant croc remained a mystery, however, until Sereno's team began excavating at Gadoufaoua in 1997. "People hadn't gone back with any expedition capacity since then, so not much else was collected," said team member Hans Larsson.

The 1997 dig had barely begun when the team discovered the fossilized jaws, each as long as some members of the team. The group had traveled to the siteone of the richest fossil beds in Africato search for dinosaurs. But it was immediately clear that the giant jawbones had not come from a dinosaur, Sereno said.

"We had never seen anything like it," he said. "The snout and teeth were designed for grabbing preyfish, turtles, and dinosaurs that strayed too close."

Other massive crocodiles have been reported, but Sarcosuchus imperator is the most complete specimen found so far and among the largest crocodilians that ever lived.

During expeditions in 1997 and 2000, Sereno's team found skulls, vertebrae, limb bones, and foot-long (30-centimeter) bony armor plates called scutes. From this trove of bones, the scientists were able to assemble about half of the giant croc's skeleton, providing a good picture of Sarcosuchus.

"The new material gives us a good look at hyper-giant crocodiles," said Sereno, an Explorer-in-Residence at the National Geographic Society and a professor at the University of Chicago. "There's been rampant speculation about what they looked like and where they fit in the croc family tree."

David Schwimmer, a paleontologist at Columbus State University in Georgia, said he was familiar with Sereno's discovery and was "thrilled with it" because it helps fill in the picture of giant crocs, which appeared repeatedly in evolutionary history. Schwimmer is an expert on a giant croc genus named Deinosuchus, which was prevalent in North America.

Sereno and his colleagues announced their discovery October 25 at National Geographic headquarters in Washington, D.C. The research expedition to Niger last year was funded in part by the National Geographic Society.

Wings of Silk Wings of Iron

Monarch butterflies, beautiful black-and-orange fluttering insects of the spring and summer, can be found throughout the world. North American monarchs are special, however, because they migrate incredible distances up to 3,000 miles each way. Amazingly, they fly to the same wintering grounds year after year, even though each butterfly rarely lives longer than a few months. How do these tiny creatures know where theyre going? How do they avoid getting lost, especially in strong winds? Scientists are still trying to answer these questions. Heres a list of some potential answers theyve come up with.

Most of the time, monarch butterflies are loners. They flutter around bushes and sip nectar all by themselves. However, when winter approaches, more than 100 million monarchs gather together from all over the United States and Canada to travel southward. In the spring, they gather again for their northern migration. North American monarchs travel in two main geographic groups: Those east of the Rocky Mountains migrate primarily to Mexico, while those west of the Rockies generally spend their winters in coastal California. No one knows exactly how monarchs repeatedly find the same roosting sites, but scientists have several theories.

One theory is that the butterflies orient themselves by the suns position, which relates to their interpretation of the time of day. If a monarchs internal clock indicates that its morning, for example, the butterfly will fly to the east. To test this theory, scientists collected monarchs and kept them in a controlled environment, exposing them to light at different times to shift their internal clocks. When the butterflies were released in the afternoon, they flew as if the sun were in the morning position. But monarchs are masters of navigation even on overcast days, so they must have other ways of finding the right direction. They may, in fact, have a kind of internal geomagnetic compass. In recent studies, monarch butterflies exposed to strong magnetic pulses showed signs of disorientation when released on overcast days.

Its possible that monarchs also use landscape features as cues. They simply settle down for the winter on the first suitable hillside or tree they come to which just might be the same hillside or tree that previous generations wintered upon. Monarch flocks alter their flying patterns once they reach the general area where they will winter, swooping low to find their ancestral roosts. We may never know for sure how these delicate creatures navigate, but their mysteries intrigue us; there is as much wonder in a monarchs journey across a continent as there is in a flap of its colorful wing.

|